The golden age of action movies happened in the early nineties, and Steven Segal was a demigod. I forget which, but in one of his movies, he wrote “fear of death is worse than death itself” on a mirror with lipstick as he stalked one of his villains. The villain came along and read it, became petrified with fear, and then died a few moments later after getting his balls blown off by a shotgun.

***

I retired at age thirty-seven. Just to be transparent, I should tell you that I’m jerrymandering semantics quite a bit: my former supervisor would use a different word than “retired,” and I’ll eventually need to make more money, so my retirement is finite. However, regardless of labels, right now, I’m on top of the world. Decades from now, when they ask me about the best time in my life, I’ll tell them about the 2016 holiday season. I’ll tell them about how I lost my job right after my birthday and I’ll make mention of the fact that I walked into October with the biggest shit-eating grin that’s ever been worn. I’ll tell them that in the twilight days of this year, my life changed permanently.

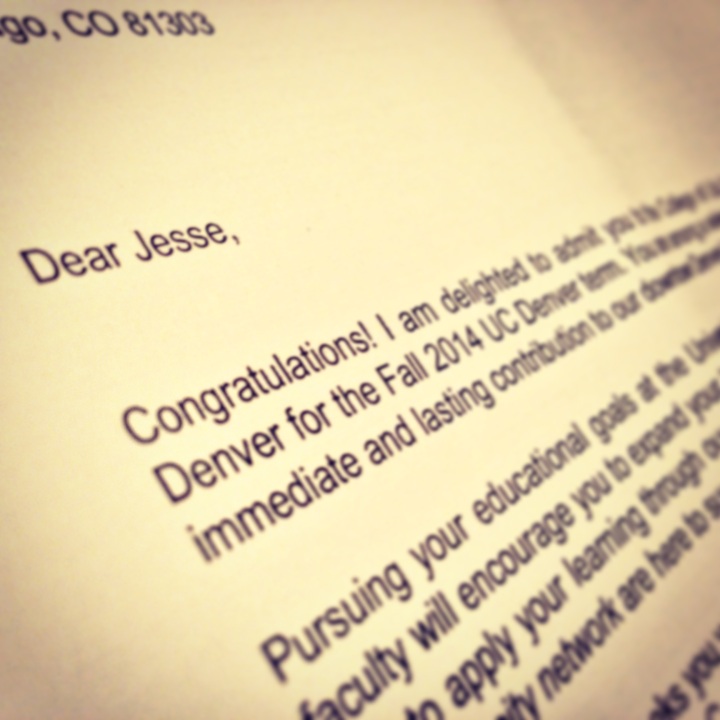

I’ll need to catch you up before you’ll understand fully. For the last sixteen years, I sold my soul daily to the oilfield. The money was good, but I loathed my occupation—it felt like socially accepted prostitution. My true opinions had to be smothered in ignorance and kept quite as to not startle the rednecks, and every professional moment was a lie lived. I went to work day after day as a sheep dressed in wolf’s clothing just so the rest of the pack wouldn’t sniff me out. “Hey, look over there,” they’d say, “that man isn’t one of us. He’s different and he writes things just for fun. He thinks too much. Get the tar, get the feathers.” My discontentment was a palpable thing. It grew and grew through years of accretion because I hated what I did for a living and I hated the people who worked alongside me: assholes in zipper-free wolf suits. I snapped a couple years back. The unhappiness was a whole bale of hay on my camel’s back. I made some changes and I faced a few things honestly. I went back to school and I started to write for real. I kept my job to pay the bills, but I was just going through the motions. A layman would say that I didn’t give a fuck. My performance was laughable but I was still the best at what I did because, frankly, my left testicle was smarter than my competitors. And I waited. I just waited and waited for the end to come. Every day was purgatory while I waited for the axe, and then when it finally came, life exploded: it exploded in a good, cathartic way, like the victorious bombs of flame that blossom in fanfare at the end of every Chuck Norris movie. I’m walking away from the oilfield in slow-motion as my past life burns behind me. I won’t even blink when the wind from the explosion tousles my action-hero hair. Boom bitch, I win.

Just to be honest, I’ll put in writing the valid point you’re saying to yourself right now: if you hated your job so much, why didn’t you just quit? The short answer: I was a coward. After that many years of indentured service, I became institutionalized just like a Shawshank inmate. The outside world was a scary place full of uncertainty and murky paths. My job, even though I hated it, seemed like the lesser of two evils so I never mustered the courage to leave on my own. It’s pretty pathetic and it’s hard to admit, but if you’ve lived a lengthy life, I’m sure you can relate. I’m sure there were things you should’ve done that you never did because fear of the unknown kept you “safe.” So don’t judge me too harshly.

Even though I wanted what came to me, those first few days were hard. Losing my job was like breaking up with a bad partner. You know in your heart that he or she is the problem, but he or she is too narrowminded to admit it. He or she thinks that you’re the problem, despite all the evidence to the contrary, and you never get the validation you need from you ex. It’s frustrating. There were tears and middle fingers held high, appalled laughter and regret and happiness, all mixed together like a confused soup. However, I had my family. When I lost my job, it felt like a too-taunt cord was severed quickly, it felt like freefall. Life was frightening chaos for a while, but it didn’t do a damn bit of harm because my girls came in and set things right. My cold teenage daughter warmed with love and encouragement. She supported me. Cacti rarely bloom, but when they do, their flowers are extra special. My eight-years-old daughter told me that everything would be okay. That’s her truth because for her, everything really is okay because I always make it so. And my wife came through. She asked me how long it would take to graduate if I didn’t go back to work. She asked me how long it would take to write a book. Those questions felt like mana from above and my vision always clouds when I think about her support because I might’ve crumbled without it. There’s really no way to fail when I have those three girls pushing from behind.

I don’t care if this reads like a cliché, but I’m one of the lucky ones, and not just for the obvious reasons. I was just one of thousands who lost his job. The oilfield is dying. Some people who’re still in it will tell you otherwise. They’ll say that it’s coming back, that the bust is turning to boom, but they’re wrong. Sure, it’ll come back for a while early next term as commodity prices and greed surge, but it’ll be short lived. The oilfield is a feast or famine world, as many know, but what they don’t see is that the feasts aren’t as good as they used to be, and the famines worsen as the generations pass. Three steps down and two steps up still leads you down. This impending “boom” is nothing more than a final gasp before a drowning industry goes under. Who knows? Maybe I’m a bit too fatalistic, and maybe big-oil can kick to the surface three or even four more times before death comes. Whatever. The important takeaway is that death is coming, and most of the displaced cogs like myself don’t have my advantages. They don’t have means or education, they don’t have dreams. The oilfield is their life; for me, it was a means to an end. I didn’t lose any of my identity when the axe fell, but I know men who have. Just last year, if you would’ve walked up to one of these men and asked “what are you?” most of them would’ve lead with their job title. If you do something for long enough, it becomes part of you, you become it, and when it’s taken away, there’s nothing left besides feelings of inadequacy and depression. I despise the oilfield as I mentioned and I have similar feelings for the archetypical oilfield-man, but I also have boundless empathy for all the good people who’ve lost and who’re anguishing. Right now, there’s an entire demographic suffering through an identity crisis, but luckily, I’m not part of it. I’m the crab who clawed his way to the top of the bucket and escaped.

You see, throughout all those days I sold my soul, I never let the oilfield get into my soul, if that makes sense. I never acclimated to oilfield culture, I was never assimilated. Even before my birthday, this is how our conversation would’ve gone:

“What are you, Jesse?”

“I’m a father, husband, writer.”

“Okay, but what do you do?”

“I make sure my family is good and I write things. I work in the oilfield, I guess, but that’s about as important as my job replacing the toilet paper when it runs out.”

See what I mean? The secret is this: fuck it. Fuck all of it. Work to live, never live to work because that’s not living. Don’t get tied up in your day-job because what you do to buy toilet paper isn’t who you are. Don’t feel bad if you’re just now getting it; plenty of people never do. The trenches I escaped are still there. There are still people working there, blaming their woes on my departure and giving birth to rumors. Those fools are just crabs still stuck in a bucket, jealous of my freedom, clawing at their coworkers with negativity as they long for escape. They’re just like I was: they hate where they’re at but they’re too afraid to seek greener pastures. I know how that feels, intimately. But that’s not my reality anymore, and I have a plan.

Plan “A” would be to take a year off and plow through my degree, earning money as a freelance writer along the way, and then lock down a remedial job of some sort while I earn my master’s. Maybe I’d publish a book along the way. Plan “A” is super sparkly, but it’s not too realistic. Plan “B” is to take a full-load for the spring semester and take just six months off work. I’ll find a job if I need it and it’ll only push back my graduation by a semester or two. This is where I’m headed. I have an internship at a local newspaper set up for the spring and it isn’t a stretch financially or morally to go through with it. It’s painfully exciting. Plan “C” is by far the most realistic: get a job, peck away at the degree. Wait to be a writer, wait and wait longer because it’s safe and secure and that’s what the fear says to do. My resume is on point and I’ve already turned down a few jobs. I had an interview this morning for a position that’d be a step up from the one I just left. Things went well. It has the six figures we’re programed to chase and all the benefits that lead away from unsure dreams. I have another interview the first week in January. This job would be a step up from the step up. I set these things up and chase things I’ve already had because I’m afraid to jump; I’m climbing down the cliff slowly.

But what happens when one of these jobs is offered to me? It isn’t unrealistic to think that one of the two could be mine, and they’re both perfect. They’re local; they’re in a field that isn’t dependent on barbarian controlled fossil fuels; they pay ridiculously well. Will I be able to turn one down, and even if I could, should I? “Actually, sir, never mind. You can keep your perfect, realistic job because I want to be a writer when I grow up. I don’t need all your stupid money and benefits because I’m an artist damn it!” Right… that’s bullshit. My hypocrisy is alive and well, and of course I’ll take the money. Of course I’ll go back to selling my soul, albeit to a different devil, because principal and freedom just look good on paper. I like to travel and I like brand names and I like the crust of the upper-middle class because it tastes better than generic foods from the grocery store. But jumping on a job is just probably what I’ll do. I have until January seventeenth to make a final decision regarding my spring semester schedule, and that leaves me where I am, right here, right now: In the best months of my life, telling myself that the possibility is finally a reality, that maybe I can be a writer without waiting. There: you’re all caught up.

This is going to sound trite, like a middle-aged man pining for younger years; I promise it’s anything but. I never had a young adulthood. My wife and I were married before she was legally allowed to drink, and we had a baby on the way. I went from living in my dad’s house with nothing more to my name than a burgeoning drinking problem all the way to living in my first mortgaged home with a new car. It took me about three months. A baby will light that proverbial fire under your ass. The point is that my wife and I skipped that whole “find yourself in your early twenties” thing. We didn’t travel the states in a piece-of-shit station wagon, we didn’t try to find some little town thousands of miles from home that we could call our own, and we didn’t spend the time trying to find our passions. The missed romance of such formative years is regrettable, but it wasn’t all bad. We got a head start on life—for it, we have investment properties to show, a nest egg for periods in life just like this one, and a lifetime of adult experience that many of my peers are just now jumping into. So, it is what it is. I’m not going to make some vain attempt to recapture a part of life that I missed: I’m just going milk out of these winter months as much enjoyment as possible because I feel like I deserve it.

During these holidays, I have true freedom. The fall semester just ended, so this period is the first time in my adult life wherein I have nothing to do. No class, no job. And oddly enough, this period is the first time in my life that I don’t have a boss. Seriously. I went from living with a parent directly into a career so there was always an authority figure looming. There was always someone who could call and ask me to do something. But not right now. I’ve untethered myself from my cell phone. The first time I left it behind, I took my youngest daughter to the park. I told her that I didn’t bring my phone on purpose. I told her that I wasn’t available to anyone else in the world besides her, and the smile I saw was love painted into an expression. Hell, that single moment was worth all the stress that came along with my severance. And that’s how I’m living life right now. For me, for my daughters and wife, for the fucking moment. I’m watching cartoons and eating Lucky Charms. I’m working out like a beast and growing my beard in accordance. I’m cleaning and cooking (as it turns out, I’m quite the domestic diva), and for once, I’m writing daily. The twenty-five hundred words you just read equal only half of what’s come out of me today, and it honestly feels like I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing. It’s wonderful. These three months will surely turn into halcyon days of remembrance and I’m not going to make the mistake of cherishing them less than I should while I’m living in this temporary-retiree paradise. And that’s why I wrote this. These five pages I just banged out are nothing more than a sticky note reminder, a string tied to my finger: Jesse, you have what you wanted. There’s no excuse to be unhappy. Don’t worry about what’s coming because it’s manageable, and just enjoy this time off because it’s okay, and it’s deserved.

However, I need to write something for you as well, some nugget of verity. So, here it is. Steven Segal was right. All those days I waited for the end were far worse than the end itself. There were months and years of “something’s got to give” feelings before something finally gave, and when it happened, it didn’t carry with it the pain I saw coming. The world didn’t end and I didn’t lose who I was. My family didn’t reject me and I wasn’t instantly homeless. I wasn’t shunned by the rest adulthood like some beggar pariah and I found the support I needed and the tools that’ll take me forward within myself. Everything, every bit of it, has been awesome. So, if death is coming for you, if an end of your own is forthcoming in the near future, just deal with it when it comes. All the days between now and then are for living, and that’s not something you can do if you’re not right here, right now, where you’re supposed to be.